Should I stay (Short-Term) or should I go (Long-Term)?

Doug Drabik discusses fixed income market conditions and offers insight for bond investors.

This week’s discussion is a follow-up to last week’s overview of the elongation of the economic cycle. There are many mitigating factors affecting the economy, some of which can sway sentiment, influence economic data releases, and ultimately interest rate direction. Amassed liquidity is impacting the economy and individuals’ financial positions. The following chart bears repeating as it displays the vast cumulation of money market funds - a cash alternative. Is this a strategic position or one of uncertainty?

There is over $6 trillion in taxable and tax-exempt money market funds which is nearly double the 20-year average. Uncertainty can trigger an investor’s investment choice as they opt for a sort of “parking place” with their money while seeking out a more profitable long-term plan. Oftentimes, investors equate “short” with being more conservative. In reality, staying short is not necessarily conservative. The only way to know whether the maturity of an investment is conservative or not is to know what interest rate the future will bring. Since I can safely say that none of us can always accurately predict the future, staying short-term becomes a statement of choice.

Think of it like this. If you absolutely, without any doubt or space for error knew that interest rates would be lower over the next 5 years, staying short becomes risky because you absolutely know your maturing asset will be reinvested in a lower-earning asset. The “conservative” investment choice under these conditions, would be to lock in for at least 5 years; therefore, being locked into the highest return possible over the period. Staying short-term or long-term is in essence a call on future interest rates.

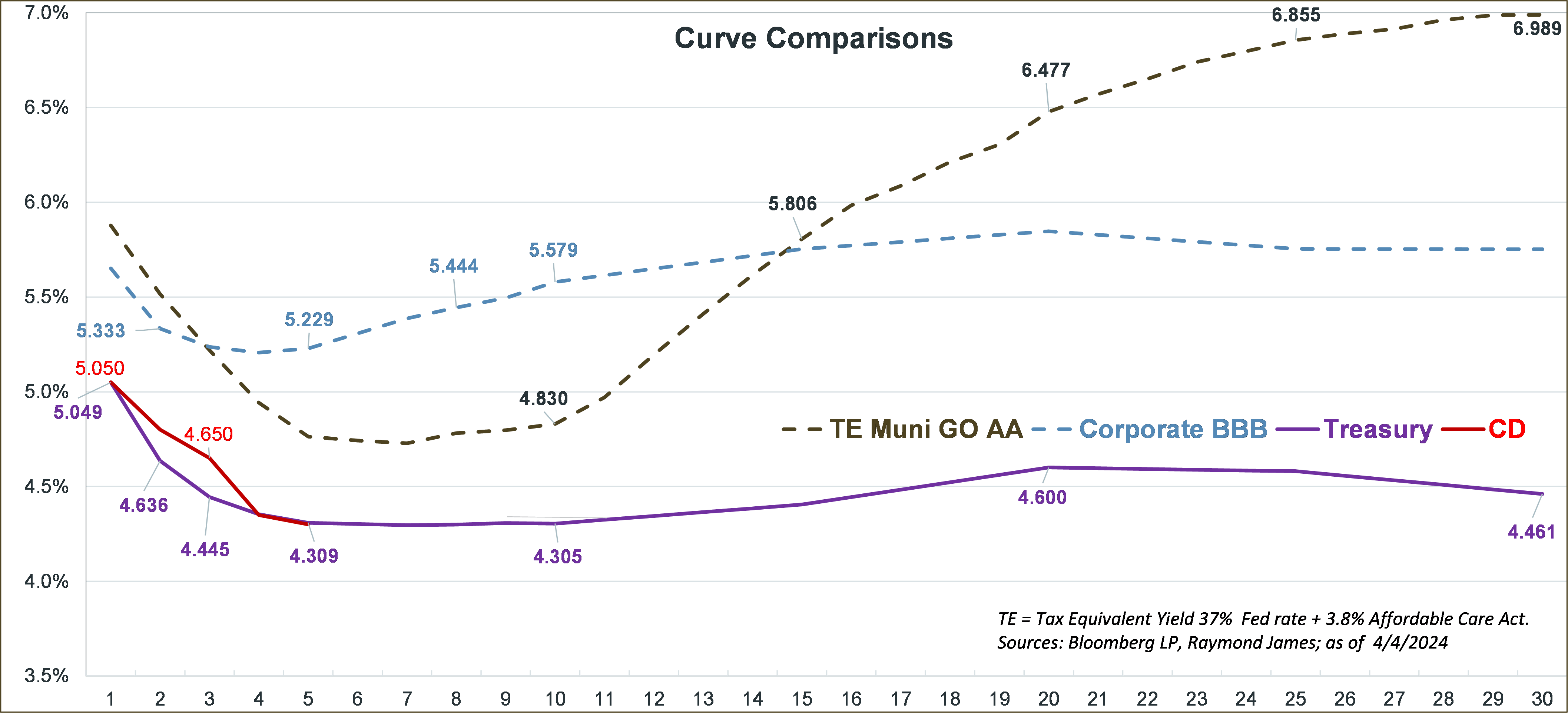

Perhaps the more plausible explanation for the mounting accumulation in money markets is investors’ appetite to optimize income. For the last nearly 1.5 years, this strategy has worked. The Treasury yield curve has been inverted – – meaning that short-term maturities offer higher rates than long-term maturities. If you can earn 5%+ yields with little interest rate risk, why not roll short-term money? Money markets typically own very short-term securities requiring constant reinvestment into new short-term securities as the investments mature. This means that the yields offered by money market funds are typically highly correlated with short-term yield and by extension, the Fed Funds rate.

If our lifetime investment horizon was merely a year or two, this plan would seem sound; however, most of us have to strategically plan for roughly 40 years of investing toward retirement - somewhere around age 25 to retirement at age 65. During that investment span, there are no guarantees on interest rates. We only need to look at the last 40 years to realize that investors bound to those investing years have been in a continuous falling rate environment. Their greatest opportunity to lock into the highest rates during their investment tenure was at the beginning.

The intermediate-to-long-term rates available today have not been available in nearly two decades. Admittedly, it may be hard to focus on a long-term investment plan when what seems conservative short-term alternatives are offering 5%+ returns. Nevertheless, the continuance of those 5%+ money market returns has no guarantee nor does the availability to lock into high intermediate-to-long-term rates. Investors who miss the window of income opportunity available in longer maturities are not guaranteed to see these yields ever again over their lifetime’s investment span. Investors stuck holding short money market funds when the Fed reverses policy and rates begin to fall will likely be faced with both lower money market yields and fewer long-term attractive income options.

Should I stay short or go longer? If your investment strategy is about optimizing your future retirement income, it may be time to lock in for longer and optimize on today’s long-term opportunities.

The author of this material is a Trader in the Fixed Income Department of Raymond James & Associates (RJA), and is not an Analyst. Any opinions expressed may differ from opinions expressed by other departments of RJA, including our Equity Research Department, and are subject to change without notice. The data and information contained herein was obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but RJA does not guarantee its accuracy and/or completeness. Neither the information nor any opinions expressed constitute a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security referred to herein. This material may include analysis of sectors, securities and/or derivatives that RJA may have positions, long or short, held proprietarily. RJA or its affiliates may execute transactions which may not be consistent with the report’s conclusions. RJA may also have performed investment banking services for the issuers of such securities. Investors should discuss the risks inherent in bonds with their Raymond James Financial Advisor. Risks include, but are not limited to, changes in interest rates, liquidity, credit quality, volatility, and duration. Past performance is no assurance of future results.

Investment products are: not deposits, not FDIC/NCUA insured, not insured by any government agency, not bank guaranteed, subject to risk and may lose value.

To learn more about the risks and rewards of investing in fixed income, access the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority’s website at finra.org/investors/learn-to-invest/types-investments/bonds and the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s (MSRB) Electronic Municipal Market Access System (EMMA) at emma.msrb.org.